Sunethra Rajakarunanayake's ප්රේම පුරාණය- The First Contemporay Sinhala Novel to Be Translated into French…

28 novembre 2024

Par Janaka Samarakoon

Every time I speak of this book, I can’t help but reflect that if I find myself here in Europe—far from my homeland, immersed in a culture so different from my own, shaping a destiny that was never meant to be mine—it is, in no small part, because of this book. A book I discovered at 19, offering me a radically different perspective on the sociological determinism toward which my life was, at the time, peacefully drifting.

Thiranjani Sunethra Rajakarunanayake

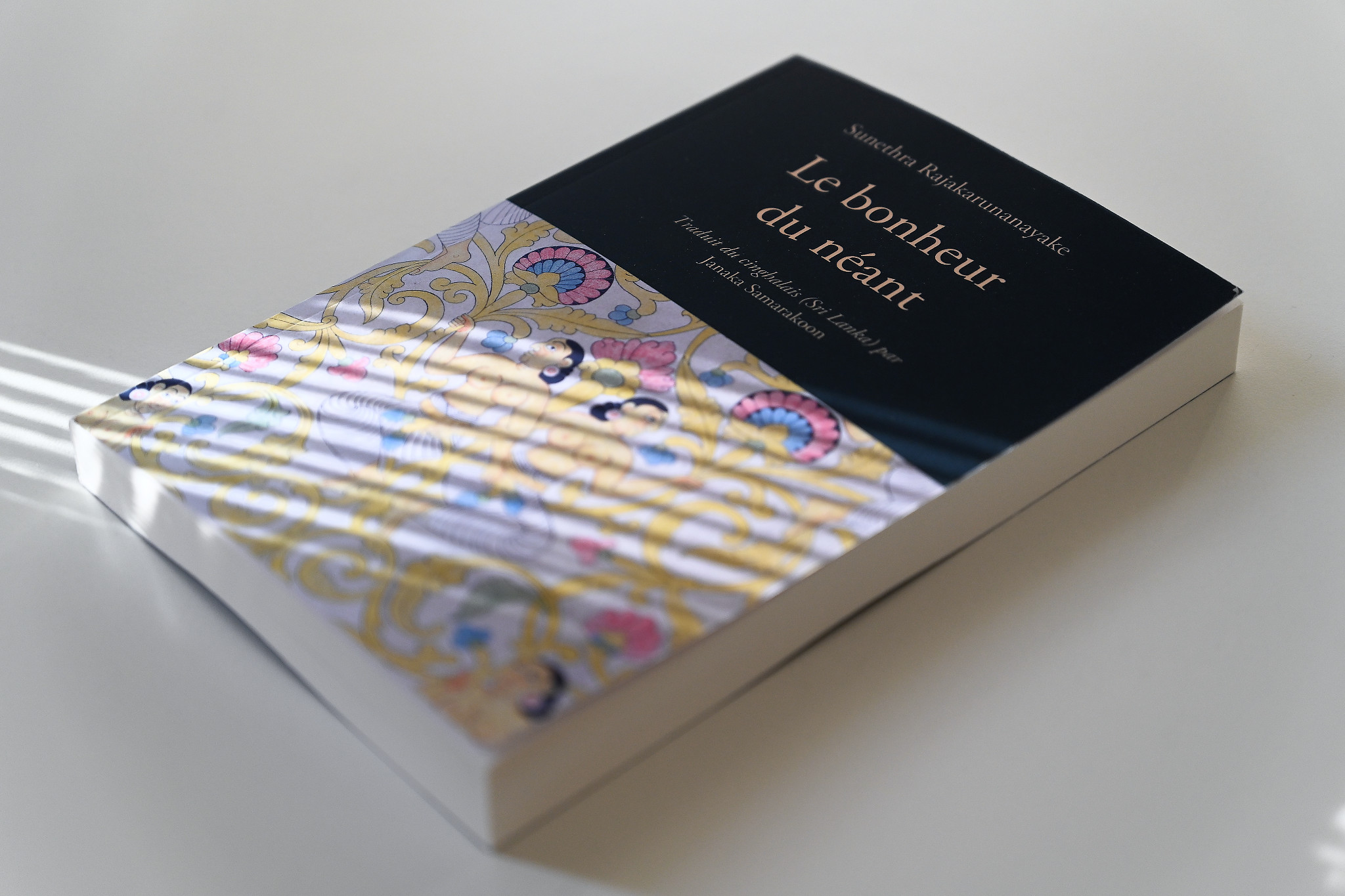

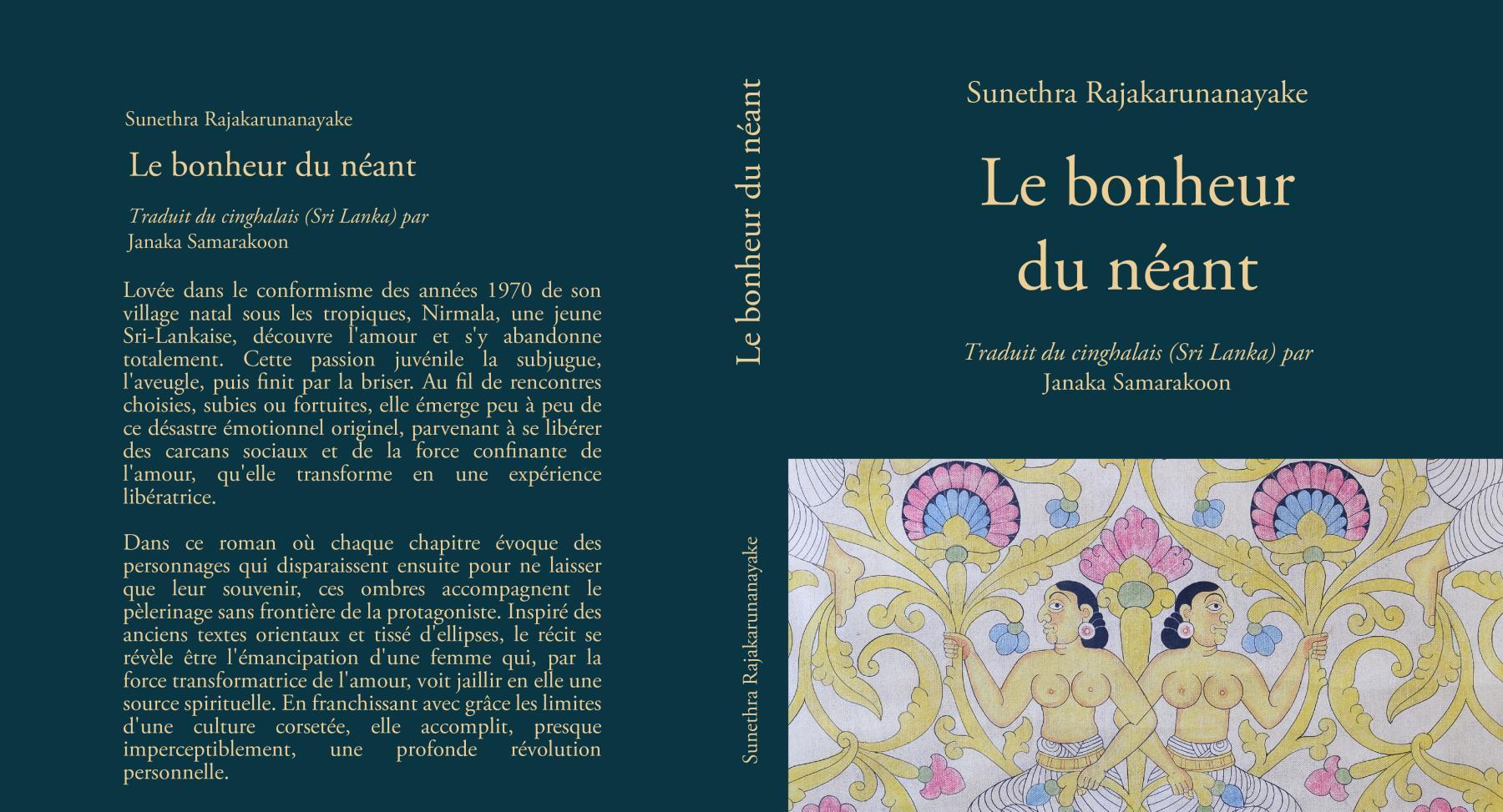

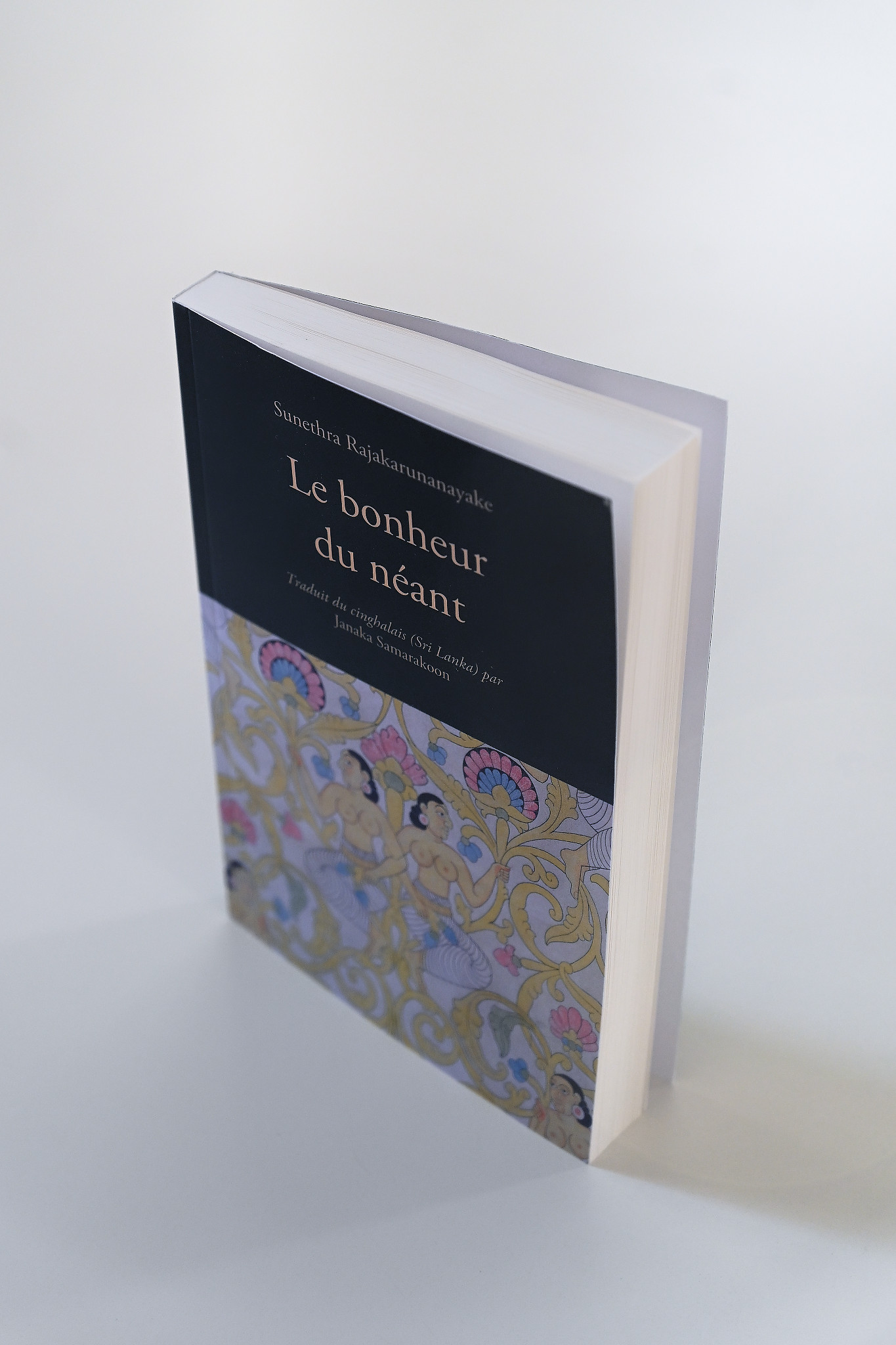

Le bonheur du néant

ප්රේම පුරාණය

ASIN : B0DPHCQ5JX

Language : French

Paperback : 275 pages

ISBN-13 : 979-8345186084

Format : 13.89 x 1.75 x 20.5 cm

Breaking Literary Boundaries

The novel first captivated me with its remarkably fluid, boundary-breaking format—a striking departure from the conventional local literary scene when it was released 25 years ago in Colombo by Vidarshana, an obscure yet daring young publisher.

It appeared to seamlessly blend fiction with non-fiction: carrying the expansive sweep of a novel, while hinting at an intimate touch of autofiction—its authenticity, however, remaining ambiguous. At the same time, it could be seen as a hybrid—part novel, part collection of short stories. Both profoundly intimate and eminently sociological, the work defies easy classification, thriving in its contradictions.

To tell the story of an atypical heroine, the author employed daring, disorienting techniques: ellipses in abundance; abrupt jumps in time and space while moving from one chapter to the next; barely signposted flashbacks, aligned like in a film; and moments where poetry effortlessly took the place of prose.

All of this serves a journey that is not only spatio-temporal—global in scope and spanning several decades—but also metaphysical: the exploration of a psyche. This nomadism, freed from all social constraints and, moreover, embodied by a woman, captivated me deeply, as I still vividly recall.

In short, this novel truly put me to the test.

A summons to the unknown

Sri Lanka.

The late 1990s.

The advent of the internet and computers, which we tried to domesticate with varying degrees of success.

A new millennium loomed on the horizon, heralded as the stage for a happy globalization.

I was barely 20 and everything seemed possible.

At that moment—both a historical and deeply personal moment— this book unfolded as a manifesto ; a plan for action. It was a breath of fresh air, a summons to the unknown. I already pictured myself wandering along the dusty roads of Uttar Pradesh or seated in a café overlooking San Francisco Bay.

At the time, I had never left my island of 65,000 km² !

And then there was love — which, like Nirmala, the protagonist, I had discovered very early, perhaps too early! Like her, I yearned to discover other expressions of love, grounded in different realities.

The Dizzying Pursuit of Freedom

Nirmala is, in her own way, a spiritual cousin of Emma Bovary. Her audacious relentlessness captivated me: not content to experience emotions through fantasy alone, she lived them fully, testing life’s boundaries. She uses her own flesh as a medium to mold, reshape, and, when necessary, break apart and begin again.

Later, I would find myself peremptorily quoting Flaubert: 'Emma, c’est moi!' In the end, I often reflected—aren’t we all, Emma, Nirmala, myself, and perhaps all of humanity, driven by the same 'inexhaustible longing for happiness,' propelled toward a horizon of possibilities yet unable to fully define what happiness truly is or when it might ever materialize?

Curiously, this very uncertainty is, in itself, a form of freedom—a dizzying, exhilarating freedom.

Nirmala set me on this path.

A Translation Adventure

I began translating this novel in the spring of 2007. I still remember working on the first pages during an artistic residency at the Abbey of Auberive in Haute-Marne. At the time, I had been studying French for 10 years and was confident—perhaps too confident—that I was proficient enough to tackle such a project.

A youthful error, like so many others… It took me 17 years to complete this work…

By the end of summer 2007, I had already finished a complete first draft of the book, which I then revisited regularly, every year or two, rewriting it entirely each time. The penultimate version was completed during the lockdown, while the final one, finished in November 2024, is, I hope, the version that truly captures what I felt when I first discovered the original text in Sinhalese 25 years ago.

A Literary Challenge

Translating Sinhala into French can feel like unraveling a Chinese puzzle! The syntax is entirely different, cultural references are often distant, and unspoken elements—those subtle nuances to be read between the lines—abound. The collective memory—both distinctly Sri Lankan and, in a broader sense, South Asian—embedded in every word of this novel offers an immense challenge to transpose.

Confronted with these complexities, I sometimes had to take liberties. Some passages might even be considered 'adaptations'—a decision for which I hope the author will forgive me. These adjustments were essential to capture the richness of the original text and render it intelligible in French.

Many Books Within a Book

This book, as you will discover, contains many books within itself. The author’s next novel, Ridee Thirnaganawa, published in 2001, is a testament to this. Broader in scope and imbued with a sweeping sense of drama, it starts from nearly the same premise but ventures into an entirely different dimension.

Ridee Thirnaganawa is my next translation project—one that has been underway since 2014!

A Rare Feast in Francophonie

This project marks a modest yet significant literary milestone: to the best of my knowledge, it is among the first Sinhalese novels translated directly from the original language into French. In 2007,when I started this project, there was one such translation: Viragaya ou le non-attachement by Martin Wickramasinghe, translated by Mandawala Pannawansa. Since then, I am not aware of many others. If you know otherwise, I would be delighted to hear from you!

A heartfelt thanks to Sunethra, who trusted me 17 years ago and continues to do so, despite the time this project has taken. She is now encouraging me to tackle her more recent novels, in French or English — a challenge I am eager to take on.

Finally, my gratitude goes to Dr. Jacques Soulié, psychiatrist, man of culture, and faithful companion for 25 years. A tireless proofreader, he has revisited this text in its countless versions over 17 years, always with unwavering generosity and patience for my stubbornness.

Happy reading!