Contextualising Kandyan Period Frescoes

2023 August 10

BY DR JACQUES SOULIÉ ET JANAKA SAMARAKOON | 22 NOV /2022

INTRODUCTION

The Sri Lankan pictorial tradition, widely recognized as the "Kandyan school" or "Kandyan style," represents a profoundly iconic body of work that thrived under the patronage of the Kings of Kandy, during the era when Kandy served as the capital of the Central region kingdom. Historically, the Kandyan period commences in 1469, marking the ascent of a local ruling authority, and perseveres until 1815, when the entire island came under British domination. However, it was only in the mid-18th century that a distinct and vibrant "Kandyan" pictorial style fully blossomed.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The city of Kandy, formerly known as Senkadagala, was founded by King Vikramabahu III, who ruled from 1357 to 1375, not in Kandy but in Gampola, the capital at that time. In 1412, Kotte became the new capital remained so until 1597. This post-Anuradhapura/Polonnaruwa period—an era spanning from 377 BCE to 1232 CE—was marked by a succession of ephemeral kingdoms. Due to continuous invasions from India which triggered the downfall of the glorious Anuradhapura kingdom, the capital cities moved southwards. During the same period, the central province, locally known as Udarata, established itself as a parallel power. Senasammata Vikramabahu ascended to the throne of Kandy in 1469 as its local ruler. Between the arrival of the Portuguese colonisers in 1505 and the dismantling of the Kotte kingdom into three rival states in 1521 by the parricidal sons of King Vijayabahu VI (1513-1521), the country faced a chaotic political situation.

A few decades later, during the reign of Vimaladharmasuriya I (1590 - 1604), the island experienced some stability as Kandy became sole the capital, except the regions now placed under Portuguese control and the Northern Jaffna kingdom, a distinct entity under different foreign rulers after the invasion of Kalinga Magha from India in 1215. During this period, the Northern kingdom was to fall into the hands of the Portuguese in 1591. The European invaders deposed King Puviraja Pandaram of the Jaffna kingdom and installed his son Ethirimana Cinkam, who pledged allegiance to the foreign power.

Under these circumntances, Kandy became the only center of resistance against the Portuguese and also earned its status as a sacred city, a position that continues to this day through the presence of the relic of the Buddha's tooth brought to the city by King Vimaladharmasuriya. The revered object is an essential symbol guaranteeing the sovereign's legitimacy.

As the guardian of this sacred object, a highly coveted status, the city of Kandy became ever since the stage for intense cultural activities. Today, it is officially known as the "cultural capital" of Sri Lanka.

EMERGENCE OF THE KANDYAN SCHOOL

The wall paintings of the Kandyan school are part of this significant cultural and religious activity that took place in the Kandyan kingdom, especially during the reign of King Kirti Sri Rajasinha (1747-1782). After a period of religious decline observable from the beginning of the 16th century on, this monarch initiated a revival of Buddhism and the arts, which led to the emergence of this painting school.

In the context of mediaeval Sri Lanka, the king and the clergy were interdependent: the king defended the faith, and the faith legitimized the king. However, due to internal dissensions and the missionary activities practices by Western colonisers, Buddhism experienced a sharp decline. There were conversions to Catholicism, even among the royals, leading to the increase of "defrocked" individuals. Lands previously owned by temples became the subject of speculative maneuvers. A new community of pseudo-monks called "ganinnanse" positioned itself, not without opportunism, as guardians of religious order but, in reality, was more focused on wealth than religious practices.

In the early 18th century, this situation led to the complete extinction of the Order of monks until the High Ordination ("Upasampada") was reestablished in 1753. In the absence of locally qualified monks, religious dignitaries from had to be called upon from Siam to reestablish the Order. King Kirti Sri Raja Singha (1747-1782), with the assistance of a local monk, Weliwita Sri Saranankara, and the Dutch, who had been present on the island since 1638 and controlled several territories once held by the Portuguese, initiated this new dynamic.

As part of this Buddhist renaissance, numerous temples were constructed or renovated throughout the kingdom, providing abundant opportunities for mural painting and sustaining the activities of local artisans. King Kirti Sri Raja Singha also undertook the expansion of the Temple of the Tooth in Kandy, a new structure built by his predecessor, King Sri Vira Parakrama Narendra Singha (1707–1739), to house the sacred relic. The vast construction project of the Temple of the Tooth served as a veritable laboratory for regional artists, presenting them with unprecedented pictorial challenges. Their response to this challenge is now known as the "Kandyan school".

Temple construction and restoration efforts extended well beyond the central region of the island to the southwest coast, central-north, and even the extreme south, albeit to a lesser extent. This new aesthetic, with its initial manifestations emerging around 1755 to 1760 (e.g., the Madavala temple), matured rapidly as can be seen in Degaldoruva (1770 – 1780), featuring a well-defined identity and sophisticated spatial deployment with extensive narrative registers. Notably, the tradition was born and reached its maturity under the reign of a single monarch and persisted into modern times.

Considering the homogeneity of works originating from different geographic locations, it is likely that the king relied on only a handful of artistic lineages or workshops who drew inspiration from the same stylistic ideals. Among the most famous were the workshops of Devaragampola Silvatenne Unnanse (Ridi Vihare, Degaldoruwa) and Deldeniya Sittaranaide (Suriyagoda).

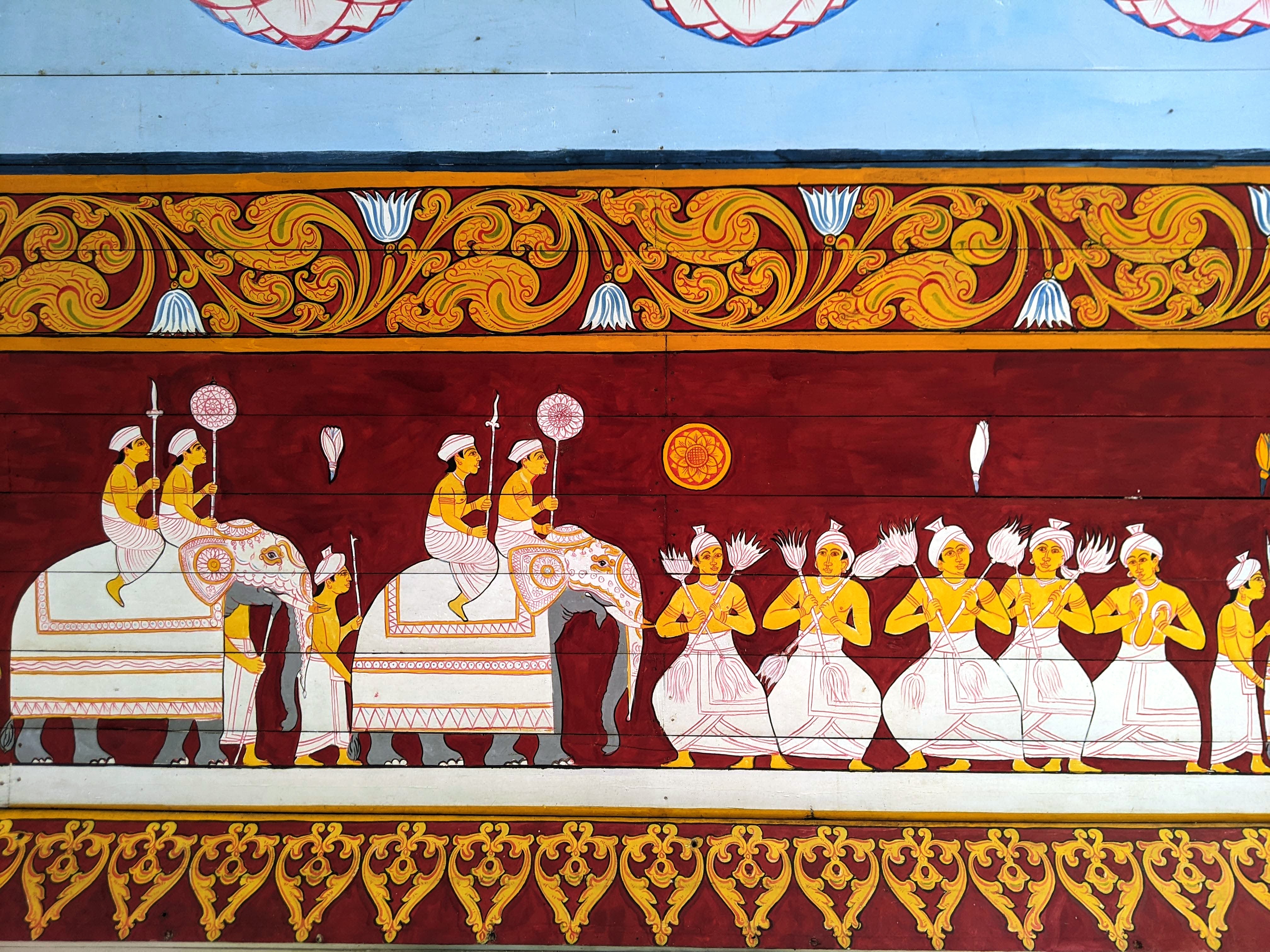

STYLISTIC TRAITS OF THE KANDYAN SCHOOL MURALS

The main features of the Kandyan style are its strong reliance on the outline, the use of lines to convey narratives, a limited color palette — predominantly consisting of yellow and red —, and a relatively uncluttered pictorial space filled with flat areas. The paintings often depict human and animal figures in hieratic styles with varying degrees of naivety, along with stylized vegetal and natural elements. They demonstrate a powerful narrative force, portraying the life of Buddha, his previous lives, his teachings, as well as myths and local history. Contemporary customs and historical events are also represented, offering an updated interpretation of ancient stories. Additionally, there are purely decorative compositions adorned with floral, vegetal, and animal motifs, reflecting a fondness for ornamentation—and even abstraction. Numerous compositions of this nature can be found on the walls and ceilings of the Temple of the Tooth in Kandy.

Perspective and shading techniques for creating volume and relief, using shadows or gradients, were not major concerns for Kandyan artists. Instead, they employed a visually arbitrary spatialization that served the narrative rather than aiming for naturalism.

Narration is, indeed, the primary function of this art, exclusively reserved for the religious sphere and utilised for the education of devotees.